Western Mexican Shaft Tombs

Author: Donna Yates

Last Modified: 08 Aug 2012

A cultural tradition known for its ceramic figurines, nearly all of which have surfaced as a result of illicit and illegal looting.

The Mexican Shaft Tomb Tradition (or the Mexican Shaft Tomb Culture) is a mortuary practice and related culture that existed in areas of Nayarit, Jalisco and Colima from around 300 BC to 300 AD. The culture(s) that produced the shaft tombs are almost entirely defined by unprovenienced and disarticulated funerary goods. Nearly all artefacts related to this tradition have surfaced as the result of illegal looting; archaeologists did not locate an unlooted shaft tomb until 1993 even though salvage excavations had been conducted on previously looted tombs since the 1960s (Mestas C. and Ramos de la Vega 2006: 164).

Tomb Descriptions and Figure Types

The shaft tombs themselves consist of a rectangular vertical shaft dug several metres into the soil and rock. This shaft typically opens into one or two vaulted or spherical chambers (Taylor 1970: 160). These chambers usually contain the remains of multiple individuals, perhaps representing reuse of tombs over time by individual families. The tombs seem to have contained large amounts of grave goods, including numerous ceramic figures that have been popular on the art market for decades.

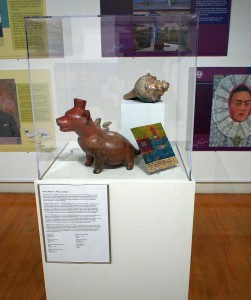

The figures have been divided into several categories, however these categories are neither mutually exclusive nor are they based on careful contextual analysis. Rather they emerged in the art market as pseudo-stylistic designation in response to the growing popularity of the figures. Thus in auction catalogues, figurines from the shaft tombs are described using such terms as: ‘Ameca’ ‘Colima’, ‘Chinesco’, ‘El Arenal’, ‘Ixtlan del Rio’, ‘Nayarit’, ‘San Sebastián’, and ‘Zacatecas’. Of these, those classified as Colima are the most famous among collectors, especially those that portray small dogs (Taylor 1970: 160).

Collecting Shaft Tomb Figures

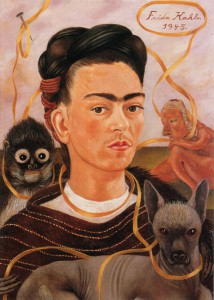

The history of the collection of Mexican shaft tomb figures is tied both to the rise of modern art and to the collecting culture that existed in California in the 1950s onwards. Mexican artists Diego Rivera and Frieda Kahlo took a particular interest in the ceramics from the Mexican Shaft Tomb Tradition. They began to collect looted figures from the tombs in the 1930s and may have prompted public interest in the pieces. A ‘Nayarit’ figure appears in the background of Kahlo’s 1945 ‘Self Portrait with Small Monkey’. Sund (2000: 735) records that by the 1950s the Shaft Tomb figures had become popular in the Los Angeles art market having been heavily promoted by such dealers as Earl Stendhal and Ralph C. Atlman. Alongside the rise in popularity of the pieces, fakes began to enter the market at this time (Kelker and Bruhns 2010: 148-152).

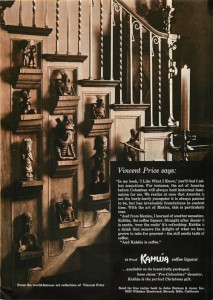

Use in Kahlua Ads

From the mid-1960s until 1995, Mexican Shaft Tomb figurines were used in advertising campaigns for the coffee-flavoured liqueur Kahlúa. This was largely the doing of a man named Jules Berman who both collected Mexican Shaft Tomb figurines and introduced Kahlúa to the American Market (Sund 2000: 735). The figure collection of actor Vincent Price was featured in one of these advertisements.

References

Kelker, Nancy L. and Bruhns, Karen O. (2010), Faking Ancient Mesoamerica (Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press.

Mestas C., Lorenza López and Ramos de la Vega, Jorge (2006), ‘Some Interpretations of the Hutzilapa Shaft Tomb’, Ancient Mesoamerica, 17, 271–81.

Sund, Judy (2000), ‘Beyond the Grave: The Twentieth-Century Afterlife of West Mexican Burial Effigies’, The Art Bulletin, 82 (40), 734–67.

Taylor, R.E. (1970), ‘The Shaft Tombs of Western Mexico: Problems in the Interpretation of Religious Function in Nonhistoric Archaeological Contexts’, American Antiquity, 35 (2), 160–69.