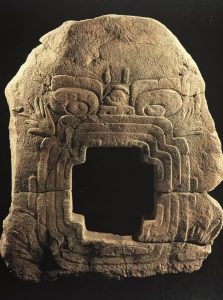

Chalcatzingo Monument 9

An Olmec Monument that was looted from Mexico and returned by the United States in 2023.

Chalcatzingo, located in the Mexican state of Morelos, represented a major regional centre during the Olmec Formative Period, with significant phases of occupation happening between 1500 and 500 BC (Grove 2008). The site was first recorded by archaeologist Eulalia Guzmán Barrón in the 1930s who documented important bas-reliefs carvings (Córdova Tello and Meza Rodriguez 2023). Since then, other reliefs have been discovered at Chalcatzingo, both by archaeologists and by looters.

There has been much archaeological discussion about the purpose and experience of the bas-reliefs of Chalcatzingo. Archaeologist Jorge Angulo V. suggested that they formed pictorial sequences (Angulo 1987), perhaps constituting a “processional arrangement” where visitors would need to “walk from carving to carving” to see them all (Grove 2008). This would mean that the sculptures were not intended to be singular units, rather they were groups to be experienced together. Chalcatzingo Monument 9 appears to fit this pattern.

Monument 9 measures 1.8 meters high and 1.5 meters wide and weighs 1 ton (Gobierno de México, 2023). It depicts “a stylized jaguar-serpent with open jaws representing the earth-monster” in the form of a cruciform mouth (Angulo V., 1987). The bottom portion of this mouth is worn, perhaps indicating that people passed through it in some way (Angulo V., 1987, p. 142). Monument 9 may have once formed a single unit with Monument 16 which is in the possession of the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City (Angulo V., 1987). It has been suggested that Monument 16, an anthropomorphic statue, may have been placed in the dark behind Monument 9, with offerings put through Monument 9’s mouth (Angulo V. 1987, p. 142).

Looting and Appearance in the United States

The exact date of the looting of Monument 9 is unknown, but it is believed to have been trafficked to the United States “by the beginning of the second half of the 20th century” (Gobierno de México 2023). Writing in 1968, Grove relates that although the piece was in a United States private collection by that time, the monument certainly came from Chalcatzingo “because various persons saw it (in its fragmentary, unrestored condition) in the yard of a Chalcatzingo farmer” (Grove 1968, p. 489). Local workers confirmed that the Monument had been found in fragments on top of PC Structure 4, and excavations conducted in the 1970s located disturbed soil that corresponded with the theft (Grove and Angulo V., 1987: 124).

Grove’s 1968 article in American Antiquity is apparently the first mention of Monument 9 in academic literature. Some reports indicate that 1968 was also the year that the monument appeared on display in the Munsun-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute in Utica, New York.

Between 30 September 1970 and 3 January 1971, Monument 9 was loaned to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for its seminal “Before Cortés” exhibition, and it appeared in the exhibition catalogue (Easby and Scott 1970: p. 79). In the catalogue, the piece is listed as being on loan from the Munsun-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute.

At some point after the Met exhibition, Monument 9 left the Munsun-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute for a private collection in Colorado, although scholars did not know the sculpture’s whereabouts. Some news outlets (e.g. Tabachnik 2023) state that the piece had only ever been on loan to the Munsun-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute from a private collection. Few details about the possession history of Monument 9 have been released to the public.

Search and Return

In 2005, archaeologist Mario Córdova Tello began an investigation to relocate Monument 9, which eventually involved a request for support from Mexico’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and other Mexican authorities (Córdova Tello and Meza Rodriguez 2023; Córdova Tello and Meza Rodriguez 2023b). The location of Monument 9 in the private collection in Colorado was confirmed in 2008, but requesting its return was complicated by numerous legal and investigative factors (Córdova Tello and Meza Rodriguez 2023). Córdova Tello reportedly worked for over 15 years to gather the required documentation to effect its return (Gobierno de México 2023b).

By 2022, Monument 9 had come to the attention of the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office Antiquities Trafficking Unit as part of a long-term investigation into the trafficking of Olmec antiquities (Tabachnik 2023). Apparently the piece was “put on the negotiating table” in November 2022 (Córdova Tello and Meza Rodriguez 2023b), and the Antiquities Trafficking Unit was able to compile a robust file in favour of return (Córdova Tello and Meza Rodriguez 2023).

The piece was returned to Mexico on 19 May 2023 (Gobierno de México 2023b).

The identity of the collectors in Colorado have not been revealed. Mexico’s Consul General, Jorge Islas López, was quoted as saying that the collectors are “super famous, super wealthy people” who “got a settlement” (Tabachnik 2023). It is assumed that either the collectors or the details of the case had some significant link to New York City due to the involvement of the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office.

[Photo by Gobierno de México]

References

Angulo V., Jorge (1987) The Chalcatzingo Reliefts: An Iconographic Analysis. In Ancient Chalcatzingo, David C. Grove (ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 132–158. http://www.famsi.org/research/grove/chalcatzingo/grove_ch10.pdf. Accessed 3 August 2023.

Easby, Elizabeth Kennedy and John F. Scott (1970) Before Cortés: Sculpture of Middle America. A Centennial Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Córdova Tello, Mario and Carolina Meza Rodríguez (2023) Portal al Inframundo de Chalcatzingo. El Tlacuache Cultural Supplement 1080, June. https://mediateca.inah.gob.mx/repositorio/islandora/object/issue%3A3460. Accessed 3 August 2023.

Córdova Tello, Mario and Carolina Meza Rodríguez (2023b) El Monumento 9 de Chalcatzingo. Arqueología Mexicana 181: 84–89. https://arqueologiamexicana.mx/mexico-antiguo/el-monumento-9-de-chalcatzingo. Accessed 3 August 2023.

Gobierno de México (2023) Chalcatzingo Monument 9 to be Repatriated to Mexico. Press Release. 31 March 2023. https://web.archive.org/web/20230803174458/https://www.gob.mx/sre/prensa/chalcatzingo-monument-9-to-be-repatriated-to-mexico. Accessed 3 August 2023.

Gobierno de México (2023b) La Secretaría de Cultura y el INAH entregan al pueblo de México el Monumento 9 de Chalcatzingo o “Portal al inframundo. Press Release. 25 May 2023. https://web.archive.org/web/20230803200423/https://www.gob.mx/cultura/prensa/la-secretaria-de-cultura-y-el-inah-entregan-al-pueblo-de-mexico-el-monumento-9-de-chalcatzingo-o-portal-al-inframundo?idiom=es. Accessed 3 August 2023.

Grove, David C. (1968) Chalcatzingo, Morelos, Mexico: A Reappraisal of the Olmec Rock Carvings. American Antiquity, 33(4): 486–491.

Grove, David C. (2008) Chalcatzingo: A Brief Introduction. The PARI Journal IX:1. https://www.precolumbia.org/pari/journal/archive/PARI0901.pdf Accessed 3 August 2023.

Grove, David C. and Jorge Angulo V. (1987) A Catalog and Description of Chalcatzingo’s Monuments. In Ancient Chalcatzingo, David C. Grove (ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 114–131. http://www.famsi.org/research/grove/chalcatzingo/grove_ch9.pdf Accessed 3 August 2023.

Tabachnik, Sam (2023) A $12 million ancient Mexican artifact has been seized in Colorado. Now the “Earth Monster” is headed back home. The Denver Post, 20 May 2023. https://web.archive.org/web/20230803193912/https://www.denverpost.com/2023/05/20/mexico-repatriation-monument-9-earth-monster-colorado-collector/ Accessed 3 August 2023.

Taube, Karl (2023) Aztec and Maya civilizations are household names – but it’s the Olmecs who are the mother culture’ of ancient Mesoamerica. The Conversation. 7 June. https://web.archive.org/web/20230607124026/https://theconversation.com/aztec-and-maya-civilizations-are-household-names-but-its-the-olmecs-who-are-the-mother-culture-of-ancient-mesoamerica-206380. Accessed 3 August 2023.