Las Bocas-style Figurines

Author: Donna Yates

Last Modified: 13 Feb 2013

A popular style of Olmec figurine said to be from the Mexican site of Las Bocas that was defined entirely by looted material that appeared on the art market.

The archaeological site of Las Bocas is located 7 km east of the town of Izúcar de Matamoros near the village of San José Las Bocas in the Mexican state of Puebla. The site is associated with the Olmec culture, a Formative/Preclassic period civilization which dominated the region from approximately 1500 to 400 BC.

In the 1960s, Las Bocas became famous for a particular style of Olmec figurine. Called ‘Las Bocas style’ after the site, this style was largely defined by the art market in response to a number of unprovenienced antiquities that were being sold by intermediaries in Mexico City. The compromised nature of the site of Las Bocas and the lack of archaeological excavation in the area mean that ceramic objects on the art market ‘represented the sole information used to evaluate the Olmec dilemma in southern Puebla’ (Paillés Hernández 2007: 4–5).

It is considered highly unlikely that all of the unprovenienced Las Bocas-style artefacts that have been bought and sold actually came from Las Bocas as will be detailed below. In a situation much like that of the contemporaneous Mexican site of Xochipala, the combination of a systematically looted site and an artefact class defined by an unprovenienced artistic style has produced a significant amount of confusion in the understanding of the Olmec generally and of the people of Las Bocas specifically.

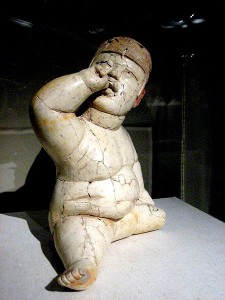

Las Bocas Figurines

The quintessential Las Bocas-style figurine is the so-called ‘baby-face’ figure, epitomized by an unprovenienced figurine now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1979.206.1134; Metropolitan Museum of Art n.d.). The piece and those like it are constructed out of white clay (or are white slipped), are hollow, and depict seated pudgy infants, some with adult traits (Blomster 2002: 177). The Las Bocas-style ‘baby-face’ figurine in the Metropolitan has ‘the typical trough-shaped eyes, downturned mouth, and fleshy cheeks’ which characterize the ‘baby-face’ type (Blomster 2002: 178). It came to the museum from the collection of Nelson Rockefeller by way of the Museum of Primitive Art. Rockefeller is listed as purchasing the piece from antiquities dealer Everett Rassiga in 1965 (Metropolitan Museum of Art n.d.). According to an article published by archaeologist David Friedel, which was based on first-hand accounts from the looters involved (personal communication), Rassiga was alleged to have been involved later in the attempted sale of a large looted Maya temple façade from the site of Placeres in Mexico (Friedel 2000: 24).

Las Bocas Style: Popularity and Consequence

Although the moniker ‘Las Bocas’ had already been applied to a particular style of Olmec figurines, it wasn’t until the publication of the book The Jaguar Children by archaeologist Michael Coe in 1965 that the Las Bocas style received international attention and acclaim (Paillés Hernández 2007: 5).

In The Jaguar Children, Coe refers to Las Bocas as being a cemetery. However several seasons of excavations conducted by Mexican archaeologist María de la Cruz Paillés Hernándezes turned up only one grave and no clear evidence of a necropolis (Paillés Hernándezes 2007: 51). Paillés Hernándezes states that only an as-yet-to-be-identified cemetery could account for the sheer number of so-called Las Bocas figurines in private collections and in foreign museums, but that the ‘cemetery’ is a ‘non-existent type of archaeological site in Mesoamerica’ (Paillés Hernándezes 2007: 52). She believes it is much more likely that ‘the high prices that pieces attributed to Las Bocas reach in the illegal market of archaeological objects may entice those who auction and sell pieces to “label” them as originating from this site’ (Paillés Hernándezes 2007: 52).

The use of ‘Las Bocas’ as a label of quality (and popularity) rather than an indication of archaeological find-spot is mentioned in much of the recent archaeological literature on the subject of Olmec iconography. For example Blomster (2003: 183) notes that by the mid 1960s, ‘Las Bocas had already gained a reputation for yielding objects of the finest caliber’, and that ‘because of the reputation of the site, the most aesthetically pleasing hollow babies that appear in museum collections invariably are labeled Las Bocas’. He recounts that early collectors of this style of figurine purchased the pieces primarily in Mexico City from intermediaries and that the Las Bocas-style artefacts ‘do not show attributes suggestive of a single manufacturing locus’ (Blomster 2003: 183). It is unclear exactly how and why the site of Las Bocas became associated with these figurines.

Archaeology at Las Bocas

In 1967 Román Piña Chan from Mexico’s National Museum of Anthropology excavated four test units at the site of Caballo Pintado which is now considered to be the main settlement of the Las Bocas site (Paillés Hernández 2007: 5). Archaeologists did not inspect the site again until 1995 and then from 1997 to 2000 when a team led by Paillés Hernández excavated at what is now termed Las Bocas-Caballo Pintado (Paillés Hernández 2007: 5).

Paillés Hernández chose Las Bocas for archaeological study precisely because it has been so heavily looted. In response to critics who felt that it was ‘too late’ to glean archaeological information from Las Bocas due to intensive looting, Paillés Hernández has stated that those very circumstances ‘urge us, from the scientific and ethical perspective, and in our role of professional archaeologists, to carry out extensive explorations at Las Bocas-Caballo Pintado, aimed at recovering every possible bit of information…’ (Paillés Hernández 2007: 16).

In 2002 several of the local workers associated with Paillés Hernández’s archaeological project gave some informal statements about the looting of the site in the 1960s. Noting that many of the small looters holes were narrow but deep, some of the workers stated that when they were boys in the 1960s they would observe the illegal excavations. They said that as opposed to the larger looters pits that were run by males, female looters were placed in charge of these ‘small excavations’ at Las Bocas (Paillés Hernández 2007: 31).

Conducting archaeological work has been difficult and even dangerous in the region. Paillés Hernández recounts that in 2000, kidnapping perpetrated by criminal gangs were a constant part of life in the area. During their excavations at Las Bocas-Caballo Pintado that year, several inhabitants of the municipality were kidnapped and near the end of excavations ‘helicopters from the state of Puebla’s Attorney General’s office would fly over [their] excavations… in an attempt to spot the criminals who customarily hid in the many caves from the nearby hills…’ (Paillés Hernández 2007: 10).

During excavation in 1998 Paillés Hernández found the fragmentary and charred leg of a hollow ‘baby-face’ figurine, however most of the figurine pieces recovered through excavation were rendered in solid clay (Paillés Hernández 2007: 44). The hollow leg is too fragmentary to classify properly and may not actually be from a ‘Las Bocas-style’ figurine (Blomster 2003: 1984). To date there is no archaeological evidence that links the site of Las Bocas to the corpus of Las Bocas-style figurines in international collections.

References

Blomster, Jeffrey P. (2002), ‘What and Where is Olmec Style? Regional perspectives on hollow figurines in Early Formative Mesoamerica’, Ancient Mesoamerica 13(2): 171-195.

Coe, Michael. (1965), The Jaguar’s Children: Pre-classic Central Mexico (New York: New York Graphic Society).

Friedel, David. (2000), ‘Mystery of the Maya Facade’, Archaeology Magazine 53 (3): 24.

Metropolitan Museum of Art (n.d.), ‘”Baby” Figure’, Website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, <http://www.metmuseum.org/Collections/search-the-collections/50005989>, accessed 17 September 2012.

Paillés Hernández, María de la Cruz (2007), ‘Las Bocas, Puebla, Archaeological Project’, FAMSI REPORTS. <http://www.famsi.org/reports/99041/99041PaillesHernandez01.pdf>, accessed 16 September 2012.