Mosaic Maya Mask

Author: Donna Yates

Last Modified: 19 Feb 2017

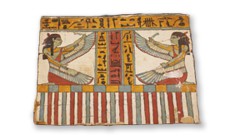

Mosaic stone mask said to have been looted from a Mexican cave and now in the collection of Dumbarton Oaks.

In 1966 Mildred Barns Bliss, the widow of a former diplomat Robert Woods Bliss and cofounder, along with her late husband, of the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection in Washington DC, purchased what purported to be a Maya mosaic mask. The story of how it was looted and moved into the US is considered by many to be unbelievable.

An unbelievable story

According to Coe (1992) and Meyer (1973), a Mexican antiquities collector named Dr. Josué Sáenz was contacted by an unknown caller who called himself ‘Gonzáles’. Gonzáles called three times and demanded that Sáenz take the first flight to Villahermosa, Tabasco (Meyer 1973:17). There Sáenz was met by strangers who convinced him to get into a small plane, the compass of which was covered with a cloth (Meyer 1973: 18; Coe 1992: 227). They eventually landed on a remote airstrip in the foothills of the Sierra de Chiapas where a group of villagers came forward with looted antiquities.

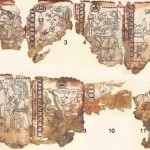

According to Coe (1992: 227; also Marhenke 2002), the villagers showed Sáenz the Grolier Codex, the mosaic mask, and some other pieces. Meyer states that Sáenz asked to take the antiquities back to Mexico City to have them authenticated but that the villagers refused, saying that he had to make his decision right there (Coe states that Sáenz was able to take the pieces to his authenticator). Sáenz offered the villagers $2,000 but they produced a Parke-Bernet auction catalogue and indicated they knew the US sale value of Mexican antiquities (Meyer 1973: 18). Sáenz then wrote a post-dated cheque for a higher amount and possession of the mask (and, perhaps, the Grolier Codex) was transferred.

According to Meyer (1973:19), when Sáenz showed the mask to José Luis Franco, the art expert and authenticator felt that it was probably a fake. Based on Franco’s opinion, Sáenz allegedly put a stop purchase order on his cheque for the piece but found it had already been cashed. Sáenz then turned the mask over to a dealer he worked with, instructing the dealer to sell it with no guarantee of authenticity. The dealer then sold the piece on to a New York-based dealer that Meyer calls ‘George Alpha’, identified here as Alphonse Jax (Dumbarton Oaks n.d.; Meyer 1973:19). The piece was moved into the United States.

Questions about the authenticity of the mask remained. Jax allegedly showed the piece to Dr. Gordon Ekholm, the curator of Mexican archaeology at the American Museum of Natural History (Meyer 1973: 19). Ekholm examined the mask under a microscope and found what he believed to be evidence that a beard had once been attached to the mask, a detail that he felt forgers would not include. According to Meyer, Ekholm’s declaration that the mask was genuine “considerably enhanced the value of the mask” (Meyer 1973: 19). The mask is now widely considered to be genuine. At this point the mask was sold to Bliss.

Connection to the Grolier Codex

Although Coe (1992: 227) has published that the mask and the Grolier codex were found together and were both part of the uncorroborated story of Sáenz in a small plane in the jungle, there is little solid evidence to support this. The codex itself was first seen in New York in 1971 in an exhibition organized by Coe and the small plane and mysterious cave are not mentioned anywhere in the literature associated with the piece at that time. When Coe was contacted by Meyer and asked where the codex came from, Coe would only say that ‘the codex was a “real hot potato” lent to the Grolier Club by an anonymous owner’ and would say no more on the matter (Meyer 1973: 36).

Meyer (1973: 40) states that a few months after the display of the codex, “George Alpha” (identified here as Jax), told him that the codex was genuine. He said that the piece had been found in a wooden box as part of a funerary group that included the mosaic mask, but that the piece had not passed through his hands (Meyer 1973:41). Meyer believed that his source was telling the truth.

It is interesting to note that the pieces do share some qualities. First, the authenticity of both pieces has been hotly debated. Second, if real, they would both date to the Maya late Post Classic period. Third, they are both tied, in some way, to collector Josué Sáenz whose story about how one or both of those pieces came into his possession strikes many as far-fetched.

Because it is unknown if the mask and the codex were found together, and because the pieces were looted, we have lost the opportunity to study what may have been an entirely unique Maya funerary context.

References

Coe, Michael D. (1992), Breaking the Maya Code (New York: Thames & Hudson).

Dumbarton Oaks (n.d.), ‘Mosaic Mask’, Website of the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. Available at: http://museum.doaks.org/Obj22723?sid=1221&x=47112 Accessed on 23 May 2013.

Marhenke, Randa (2002), ‘The Grolier Codex’, FAMSI. Available at: http://www.famsi.org/mayawriting/codices/grolier.html Accessed on 7 August 2012.

Meyer, Karl E. (1973), The Plundered Past (New York: Atheneum).