November Collection of Maya Pottery

Author: Donna Yates

Last Modified: 21 Jul 2020

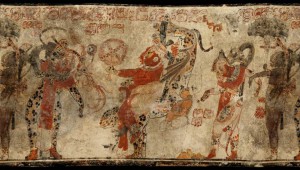

A spectacular collection of Classic Maya pottery thought to have been systematically looted from Guatemalan sites throughout the 1980s now in the possession of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

In 2010 the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston, unveiled its ‘Art of the Americas Wing’: a multi-story, multi-gallery, multi-million dollar extension focused on the artistic output of North, Central, and South America from ancient times up to the present. A prominent feature of the lowest story of the wing is an impressive group of Classic Maya polychrome pottery known as the November Collection. The collection comprises 138 pieces of jade, pottery, incense burners, effigy figures, and other objects (IFAR n.d.; Museum of Fine Arts Boston n.d.) and contains some of the finest examples of Maya artistic prowess. The MFA Collections website records the November Collection’s provenance as:

Collected between 1974 and 1981 by John Fulling, Art Collectors of November, Inc., Florida (and known as the “November Collection”); to Landon T. Clay, Boston, Massachusetts, in 1987; to MFA, December 1988, gift of Landon T. Clay.

These pieces are thought to have been illegally looted from the Petén region of Guatemala in the 1970s or early 1980s and brought into the United States without export permits (Yemma and Robinson 1997; Slayman 1998).

The November Collection was initially amassed by a Florida-based collector named John B. Fulling. According to his obituary on the website of the John B. Fulling Haitian Art Collection:

In the 1960’s John developed an interest in Mayan art, so just like Indiana Jones, off he went into the jungles of Guatemala, with guides and guns, to accumulate one of the largest collections of Mayan art in North America. (John B. Fulling Haitian Art Collection 2010).

Before he died in 2005, Fulling stated that he bought the objects through Guatemalan dealers in the 1970s and had no idea how recently they were excavated (Yemma and Robinson 1997)[1]. Public records show that Fulling created ‘Art Collectors of November, Inc’, registered on 7 April 1981 as a domestic for-profit corporation in Ft Lauderdale (Florida State Reference ID: F28816), listing himself as the president, Robin S. Fulling as the vice president, and Martin F. Avery Jr. as the corporation’s agent. It is not known when, where and how the material that came to form the collection entered the United States.

In 1987, Landon T. Clay, former chair of the Eaton Vance Corporation and founder of the Clay Mathematics Institute in Cambridge Massachusetts (Storrs 2006), bought the November Collection from Fulling (IFAR). Clay, who was a trustee of the MFA at the time and who remains an honorary trustee as of 2 April 2012, donated the November Collection to the MFA in 1988. Some reports indicate that Clay stored the collection at the museum before formally donating it (Dorfman 1998).

Although it is unclear exactly when the November Collection was imported into the USA, at least one piece of the collection had been in the country since 1975, two since 1978, and eighteen more since 1981. The first time that a November Collection piece appears to have been published was in a 1975 volume by Francis Robicsek (Robicsek 1975: 167 Figure 53). The photograph shows only a portion of the pot (now MFA accession number 1988.1168) which is listed as ‘Photograph courtesy Nicholas Hellmuth/C-78′[2]. The first reference to the November Collection by name appears in a 1978 volume also by Robicsek who reproduced four views of a pot that is now in the MFA (accession number 1988.1171; (Robicsek 1978: 34 Figure 37)). Also in 1978 a November Collection vase (MFA accession number 1988.1170) was published by Michael Coe who lists the piece as “Collection: anonymous” (Coe 1978: 124–28).

Robicsek is the primary early publisher of November Collection pieces and with the exception of the one publication by Coe[3], no other November Collection object appears in print until Robicsek’s own 1981 and 1982, volumes which appear to have been prepared at the same time in 1981. The 1982 volume specifically focuses on the corpus, referring to it as the November Collection, and depicts 22 pieces of pottery that are now in the MFA (Robicsek and Hales 1981, 1982). Neither the Robicsek volumes nor Coe’s book mention any ownership information beyond ‘November Collection’.

By the time that Clay purchased the pieces, the November Collection had developed a bad reputation among Mayanists. Indeed, upon hearing that the MFA had acquired the November Collection, Boston University archaeologist Clemency C. Coggins formally contacted Alan Shestack (the director of the MFA from 1987 until 1993) warning him that the collection was both illicit and illegal and urging him to decline the donation (Slayman 1998; Yemma and Robinson 1997). In a letter to Coggins, Shestack stated that the collection was not “exported from its country of origin or anyplace else in violation of that country’s laws” (Yemma and Robinson 1997).

Shestack’s successor, Malcolm Rogers (director of the MFA from 1994), has said that because of the MFA’s ‘lavish due diligence’ (quoted in (Yemma and Robinson 1997)), he is convinced that the museum acquired the November Collection legally. Yet Weld S. Henshaw, the attorney who conducted the 1987 legal inquiry into the November Collection for the MFA, was quoted in the Boston Globe as saying that both he and the MFA were aware that there were legality issues with the objects (Yemma and Robinson 1997). Henshaw stated that at the time he was researching the November Collection he was unaware of a 1947 Guatemalan law barring the export of antiquities without permits (see footnote) but knew about a 1987 law that required essentially the same thing. He told the Boston Globe that the November Collection was exported from Guatemala without permits (an assertion that was confirmed by Fulling according to Yemma and Robinson (1997) and that, due to civil war and local instability, Guatemalan officials were not even aware that the collection was in the United States. He advised the MFA that since Guatemala had not yet formally objected to the items being in the US, the donation was acceptable (IFAR n.d.).

An official request for the return of the November Collection to Guatemala made in the late 1980s was impeded by the unrest in the country. In 1989, then Guatemalan Cultural Affairs Officer Martina Regina de Fahsen wrote a letter to the MFA inquiring about the legality of the November Collection. De Fahsen told the Boston Globe that her request was rebuffed by Shestack and that she forwarded the correspondence on to the Guatemalan Foreign Ministry, but that domestic instability prevented immediate follow up (Yemma and Robinson 1997). The Guatemalan Government has since requested documentation from the Museum of Fine Arts that would prove that the objects were exported legally. A 1998 response to this request by Rogers states that the MFA board of trustees ‘found no basis’ for Guatemala’s claim of ownership of the November collection because the country could not produce legal title to the pieces (Diesenhouse 1998). Guatemalan officials have alleged that MFA representatives asked them how much their country would pay to have the collection returned (Atwood 2004: 147).

Archaeologists are unsure of where exactly these objects came from within Guatemala. Most believe they are the result of the looting of numerous sites rather than just one. Some November collection pieces bear emblem glyphs from the sites of Naranjo (Guatemala), San Agustin Acasaguastlán (Guatemala) (see Kerr’s http://www.mayavase.com/), others are inscribed with the names of Tintal and Nakbe in the Mirador Basin (Yemma and Robinson 1997). However, these sorts of pots may have been widely traded or may have served as political gifts between polities and thus could have been looted from anywhere in the region. It is unlikely that they will be matched definitively to the archaeological sites that they came from.

References

Atwood, Roger (2004), Stealing History: Tomb Raiders, Smugglers, and the Looting of the Ancient World (New York: St. Martin’s Press).

Coe, Michael D. (1978), Lords of the Underworld: Masterpieces of Classic Maya Ceramics (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

Diesenhouse, Susan (1998), ‘Arts in America; Looted or Legal ? Objects Scrutinized at Boston Museum’, The New York Times, 30 July.

Dorfman, John (1998), ‘Getting Their Hands Dirty: Archaeologists and the Looting Trade’, Lingua Franca Magazine, May/June, p. 29-36.

IFAR (n.d.), ‘Guatemalan Claim Against Museum of Fine Arts, Boston for Pre-Colombian Objects’, International Foundation for Art Research Case Summaries <http://www.ifar.org/case_summary.php?docid=1179695985>, accessed 1 May 2012.

John B. Fulling Haitian Art Collection (n.d.), ‘About Mr. John B. Fulling’, <http://www.johnbfullinghaitianartcollection.com/>, accessed 3 April 2012.

Museum of Fine Arts Boston (n.d.), ‘Collections’, Website of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston <http://www.mfa.org/search/collections?keyword=November+Maya+Collection+Landon+Clay>, accessed 3 April 2012.

Robicsek, Francis (1975), A Study in Maya Art and History: The Mat Symbol (New York: Heye Foundation Museum of the American Indian).

— (1978), The Smoking Gods: Tobacco in Maya Art, History and Religion (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press).

Robicsek, Francis and Hales, Donald M. (1981), The Maya Book of the Dead: The Ceramic Codex (Charlottesville: University Museum of Virginia).

— (1982), Maya Ceramic Vases from the Classic Period: The November Collection of Maya Ceramics (Charlottesville: University Museum of Virginia).

Slayman, Andrew L. (1998), ‘Antiquities Scandal’, Archaeology, 51(2), 18.

Storrs, Francis (2006), ‘The 50 Wealthiest Bostonians’, Boston Magazine Online, < http://www.bostonmagazine.com/articles/2006/05/the-50-wealthiest-bostonians/>, accessed 2 August 2012.

Yemma, John and Robinson, Walter V. (1997), ‘Questionable Collection: MFA pre-Colombian Exhibit Faces Acquisition Queries’, The Boston Globe, 12 April.

[1] Article 1 of Decreto No 425 of 1947 states ‘Todos los monumentos, objetos arqueológicos, históricos y artísticos del país, existentes en el territorio de la República, sea quien fuere su dueño, se consideran parte del tesoro cultural de la nación y están bajo la salvaguardia y protección del Estado,’ providing a solid date after which Guatemalan archaeological material is considered to be property of the state.

[2] Hellmuth is the Director of the Foundation for Latin American Anthropological Research (http://www.flaar.org/), an organisation that he founded in 1969 to photograph the art and architecture of Latin America. It is not clear if this vase was photographed in Guatemala or within the United States prior to its publication in Robicsek 1975.

[3] Coe wrote the forewords to Robicsek’s 1975, 1978, and 1981 volumes.