Placeres Stucco Temple Facade

Author: Donna Yates

Last Modified: 13 Feb 2015

A large Maya temple decoration that was located in 1968, a rare example of photographic documentation of the looting process.

See photographs of the looting of Placeres in our Data Section.

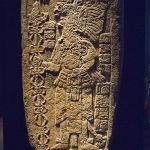

In or around 1968 a massive, well-preserved stucco temple facade was located by treasure hunters operating in the jungle regions of Campeche, Mexico (Freidel 2000). The massive sculptural piece is decorated with the head of either an unknown Maya lord (Freidel 2000) or the maize god (Museo Nacional de Antropolgía n.d.) wearing an elaborate masked headdress. On each side of the lord are heads and upper bodies of elderly Maya gods holding glyphs. The god to the left holds the glyphs for ‘black’ and ‘yellow’ and the god on the right holds the glyph for ‘reed’ and an image of a jaguar (Museo Nacional de Antropolgía n.d.). According to the finders, the facade had been found at the little-known site of Placeres and had appeared to have been intentionally buried by the ancient Maya (Freidel 2000). Placeres, which was first recorded by Sylvanus G. Morely in the 1930s, is a Late Classic Maya site located in the jungle of the Mexican state of Campeche about 35 miles east of the major Maya city of Calakmul near a former chicle station of the same name.

The treasure hunters allegedly notified their contact, the late Everett Rassiga, an antiquities dealer, of the discovery (Freidel 2000). Based on several interviews, Karl H. Meyer (1973) records that ‘Henry Beta’ (a pseudonym; identified here as Rassiga) obtained photographs of the façade in situ and offered them first to Mexico-based collector Josué Sáenz, who is linked to the trafficking of the Grolier Codex (Meyer 1973: 22). Sáenz turned down the piece but Rassiga felt he could find a buyer in the US so he ordered the piece be looted. In an operation that Meyer reports as costing more than $80,000, an airstrip was cleared and a plane was flown in from Florida (Meyer 1973:22). The facade was covered in moulds (see photographs) and sawed into transportable pieces. Meyer (1973:22) states that the saws struck stone pegs within the stucco which shattered portions of the piece. The facade was then flown to Mérida, was placed in crates that had been mislabeled, and was shipped to New Orleans and then on to New York City (Meyer 1973: 22).

According to an account published by archaeologist David Freidel, once the facade was in the USA, Rassiga approached Thomas Hoving, then director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York[1], about having the piece displayed in an upcoming exhibition entitled ‘Before Cortés’. The piece also allegedly offered to the Met for sale, with an asking price of $400,000 (Meyer 1973:22). After reviewing the piece with museum vice director of operations Joseph Veach Noble, Hoving decided to notify Dr Ignacio Bernal at Mexico’s National Museum of Anthropology of the possible major theft from a Maya site (Meyer 1973:24; Freidel 2000). According to Meyer’s account, Bernal visited the Met and determined that the façade was Mexican cultural property. When he asked who was selling the piece, Hoving informed him verbally that it was against Met policy to name the names of dealer, but then motioned with his chin to a slip of paper in his breast pocket that bore Rassiga’s name (Meyer 1973: 25).

Noble then called Rassiga back in to the Met, presented Bernal, and informed the dealer that they would not be displaying the façade and that they felt it should be returned to Mexico. At this point Rassiga allegedly suggested to the shocked Bernal that he felt that someone should pay for the $80,000 he spent getting the piece to the US (Meyer 1973: 25)[2]. Bernal notified Mexican authorities who determined that Rassiga owned a house in the Mexican city of Cuernavaca, Morales. They allegedly contacted Rassiga and informed him that his home would be seized if he did not promptly return the facade (Freidel 2000). Rassiga subsequently returned the facade to Mexico. It is now on display in the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City (Museo Nacional de Antropolgía n.d.).

The facade having been returned, legal proceedings were not pursued, however the Mexican government asserts that the export of the facade was illegal under Mexican law (Museo Nacional de Antropolgía n.d.).

The looted stucco facade from the site of Placeres, Mexico (from the website of the Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City)

In the mid-1980s, archaeologist David Freidel obtained a series of photographs reportedly taken by the man ‘who had been sent to oversee the clearing, cutting, and shipping of the facade to New York’ (Freidel 2000). The forty-seven photographs, reproduced on our Data section with the permission of both the original photographer and David Freidel, provide helicopter- or small plane-based views of the site of Placeres and the building that the facade was found within. They show all of the known iconographic elements of the facade in situ protected by a blue tarp, as well as some elements that were either not moved or destroyed during the removal process. The facade is pictured being covered in plaster for its protection and then sawn into several large pieces for removal and transport. Finally, the central mask is pictured lying on a surface, both with the stucco protective layer and with the stucco removed.

References

Freidel, David (2000), ‘Mystery of the Maya Facade’, Archaeology Magazine 53 (3): 24.

Meyer, Karl E. (1973) The Plundered Past. (New York, Macmillan).

Metropolitan Museum of Art (n.d.), ‘Collections: Everett Rassiga’, Website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, <http://www.metmuseum.org/search-results?ft=Rassiga&cat=Collections&rpp=100&pg=1>, accessed on 17 October 2012.

Museo Nacional de Antropolgía (n.d.), ‘Sala Maya’, Website of the Museo Nacional de Antropolgia, <http://www.mna.inah.gob.mx/index.php/salas-de-exhibicion/permanentes/arqueologia/sala-maya.html>, accessed 17 September 2012.

[1] A number of unprovenienced Latin American, North American, and African antiquities that passed through Rassiga’s hands in the 1950s and 1960s are now in the collection of Metropolitan Museum of Art. They were acquired by way of Nelson Rockefeller and the Museum of Primitive Art in 1978 and 1979. One of these is the famous Olmec ‘Baby Figure’ said to be from the site of Las Bocas as well as some West Mexican Shaft Tomb style figurines, and Mimbres pottery (Metropolitan Museum of Art n.d.).

[2] Meyer states that Bernal was provided with three different proveniences for the façade, finally settling on the site of Calakmul. However, the piece is now known to come from Placeras and a person involved in the trafficking of the piece confirmed that the site was, indeed, Placeres. The confusion may have come from the proximity of Placeres to Calakmul and the possibility that some looting was done at Calakmul as well at the time (as claimed by this informant).