South Pole Exploration Artefacts Taken from Campsites of Robert Falcon Scott

Author: Donna Yates

Last Modified: 06 Feb 2013

Since the main Antarctic Treaty came into force in 1961, sites associated with the exploration of the continent have been protected. Items stolen from these sites have been subject to voluntary return.

On 17 January 1912, a group of explorers led by Royal Navy Officer Robert Falcon Scott arrived at the South Pole only to find that a Norwegian team led by Roald Amundsen had beaten them there by a mere thirty-three days. Amundsen and Scott had been engaged in a race to become the first human to reach the pole.

In his journal, Scott recounts spotting the remains of one of Amundsen’s camps on 16 January, stating:

‘The worst has happened, or nearly the worst… The Norwegians have forestalled us and are first to the pole. It is a terrible disappointment, and I am sorry for my loyal companions… All daydreams must go; it will be a wearisome return.’

(Scott, journal entry for 16 January 1912, p. 543–544)

He said that the day he actually reached the pole was ‘horrible’ and reported that he had not slept the night before due to shock and disappointment: ‘Great God! This is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have laboured to it without the reward of priority’ (Scott, journal entry for 17 January 1912, p. 544). Scott and his party left the pole on 19 January and after two months of struggle, starvation, and two deaths, the three remaining explorers made their final camp on 19 March. Scott is thought to have died on 29 March 1912, or perhaps a day later, based on the final entry in his diary. He is thought to have been the last of the men to die. On 12 November 1912, a search party located the bodies of Scott and his companions. They recovered the expedition’s records and then buried the tent and bodies under a cairn of snow, marking it with a rough wooden cross.

Cape Evans camp and Protection of Hut Sites

Although the final resting place of Scott and his team is now inaccessible, several other sites associated with their journey are well-known and have been periodically visited by Antarctic adventure tourists. In particular, Scott’s base camp at Cape Evans (Ross Island, 77° 38’ S, 166° 24’ E) has been a site of constant interest. The Cape Evans campsite is an ‘Antarctic Specially Protected Area’ (ASPA) under the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS), a designation which was established when the main international Antarctic Treaty came into force in 1961 (Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty n.d.). ASPA sites are protected against development and tourists require a permit to visit the sites. Artefacts may not be taken from them except for approved conservation. However, according to Stuart Prior of New Zealand’s Antarctic Policy Unit, ‘hundreds if not thousands of items’ have been taken from these protected Antarctic expedition huts (Prior quoted in the Seattle Times, 1999).

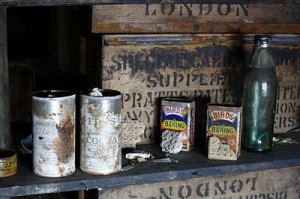

The Cape Evans campsite is managed by the Antarctic Heritage Trust, a non-profit organization devoted to conserving sites of historic exploration to Antarctica’s Ross Sea Region (Antarctic Heritage Trust n.d.). They describe Scott’s Cape Evans camp as an ‘iconic base’ with ‘8500+ artefacts associated with it’, of which around 5000 have been specifically conserved by the Trust (Antarctic Heritage Trust 2011: 4-5).

Discovery Hut

Other sites of Scott’s expedition are known and visited by researchers and tourists. Discovery Hut, built during Scott’s 1902 Antarctic expedition and located on Hut Point, Ross Island (Headland 2009), about 300 metres from the modern McMurdo Base, was rediscovered by a US expedition in 1956. Discovery Hut is also an ASPA (specifically ASPA No. 158, Historic Site No. 18 (National Science Foundation 2012)). As with other ASPAs, ‘No historic relic or artefact shall be removed from [Discovery Hut], except for the purposes of restoration and/or preservation and then only in accordance with a Permit’ (NSF n.d.: 3). Souvenirs were taken from among the preserved artefacts at the time of the hut’s rediscovery and have continued to be taken by visitors in the years since the 1961 Treaty banning such actions went into effect.

For example, Australian author Thomas Keneally has admitted to one instance of theft at Discovery Hut. In 1968 he stole a large biscuit from a tin on the hut’s floor (Chipperfield 2003). He called the action evidence of his own past ‘vanity, venality and folly’ (Keneally, quoted in Chipperfield 2003), and in 2003 he returned the biscuit to Antarctica via the Antarctic Heritage Trust at McMurdo. Although a stolen biscuit might seem relatively minor, in the years since its rediscovery, Discovery Hut has been robbed of much of its contents, including ‘sledges, skis, penguin skins, and homemade chessmen’ (Chipperfield 2003).

Hut artefacts from Christie’s sale returned to Antarctica

In 1957 John Claydon[1], a former Royal New Zealand Air Force pilot removed items from several historic expedition huts. These included leather sledge straps from Discovery Hut, a candle lantern from a hut associated with explorer Ernest Shackleton, a coat hook from Scott’s Cape Evans base camp hut, and a beaker and some bottles also from the Cape Evans camp (Associated Press 1998). Specifically, the coat hook came from what was known to be Scott’s personal cubicle and the bottles were from the cubicle of explorer Edward Adrian Wilson (Associated Press 1998). Claydon brought these items back to New Zealand as souvenirs (Associated Press 1998). Claydon has stated that by the time his own expedition reached Scott’s huts, they had been ‘pretty well cleared out’ and that ‘everybody took away souvenirs, there are thousands of them all over New Zealand’ (Claydon quoted in Farrell 1998).

In 1998, Claydon consigned the polar artefacts for sale at Christie’s auction house, London (Associated Press 1998) and they appeared as lots 210 through 214 in the catalogue for their 17 September ‘Exploration and Travel’ sale. Sir Edmund Hillary, also a New Zealander and one of the first two men to reach the summit of Mount Everest who was also very involved with polar exploration, spoke out against the sale, stating that the huts from which the artefacts were taken are sacred monuments (Associated Press 1998). Both the British Foreign Office and the New Zealand Government contacted Christie’s and requested ownership and provenance data for the artefacts (Associated Press 1998). Although the objects were removed prior to the 1961 treaty, the area they were taken from is under the territorial stewardship of New Zealand and it was thought possible that other restrictions against their removal may have been in place in 1957. Some commentators felt that while the removal took place before the implementation of the treaty, by offering polar artefacts taken directly from Antarctic huts, Christie’s was engaged in ‘woeful ignorance of or merely disregard for the spirit of the treaty’ (Farrell 1998)[2].

Christie’s defended their decision to accept the consignment of the polar artefacts for sale. Associate director Nicholas Lambourn noted that in 1901, Scott himself had taken a flag from the hut of a prior expedition and that Scott and others purposefully left items for later explorers to use (Farrell 1998). He further argued that in 1957, the huts were in poor condition and the removal of the artefacts may have ensured their preservation[3]. However, in seeming contrast to this preservation argument, Claydon stated that the artefacts had been sitting in his garage for decades and that he ‘just wanted to get rid of the stuff’ (Claydon, quoted in Farrell 1998). A few days later, officials from Christie’s announced that although they were satisfied that the consignor had title to the artefacts, Claydon had withdrawn the pieces from auction (Associated Press 1998). The items were originally slated to be donated to the Scott Polar Research Institute at the University of Cambridge, but in 1999 they were returned to their respective huts in Antarctica (the Seattle Times 1999).

References

Antarctic Heritage Trust (n.d.), ‘Website of the Antarctic Heritage Trust’, <http://www.nzaht.org/>, accessed on 9 August 2012.

Antarctic Heritage Trust (2011), ‘Annual Report & Financial Statements’, Prepared Report (Christchurch), <http://www.nzaht.org/content/library/AHT_Annual_Report_to_30_June_2011.pdf>, accessed on 9 August 2012.

Associated Press (1998), ‘Christie’s takes South Pole artifacts off the auction block’ Associated Press, 14 September.

Chipperfield, Mark (2003), ‘Keneally takes stolen biscuit back to Scott’s Antarctic base’, The Telegraph, 11 May.

Farrell, Stephen (1998) ‘Author creates a storm over auction of polar artefacts’, republished on www.museum-security.org, < http://www.museum-security.org/reports/05798.html>, accessed on 9 August 2012.

Headland, R.K. (2009), ‘Historic Huts in the Antarctic from the Heroic Age’, Website of the International Polar Heritage Committee, <http://www.polarheritage.com/index.cfm/anthutlist>, accessed 9 August 2012.

National Science Foundation (n.d.), ‘Management Plan for Antarctic Specially Protected Area (ASPA) No. 158 for Historic Site No. 18’, Prepared Report. <http://www.nsf.gov/od/opp/antarct/aca/nsf01151/aca2_spa158.pdf>, accessed on 9 August 2012.

National Science Foundation (2012), ‘Designation of Antarctic specially protected areas, specially managed areas and historic sites and monuments’, 45 C.F.R. § 670.29.

Scott, Robert Falcon (1913), Scott’s Last Expedition, Volume I, arranged by Leonard Huxley (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company).

Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty (n.d.), ‘Website of the Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty’, < http://www.ats.aq>, accessed 9 August 2012.

Seattle Times (1999), ‘Stolen Artifacts are Returning to Antarctica after 40 Years’, Seattle Times, 29 January. <http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=19990126&slug=2940732>, accessed 9 August 2012.

[1] The expedition that Claydon was a part of was the first to achieve a land crossing of Antarctica and they had set up their own camp near those of prior explorers.

[2] By this, the commentators presumably meant that the treaty sets Antarctica aside as being a neutral territory, devoted to peace, science, and research.

[3] An argument commonly employed in attempts to validate of the illicit removal of antiquities from archaeological sites in developing countries.