Tomb of Minnakht Wall Paintings

Author: Donna Yates

Last Modified: 10 Apr 2025

Also known as: Wall Paintings from the Tomb of Nakhtmin

Paintings stolen from an Egyptian tomb and purchased from an Amsterdam dealer by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Minnakht (or Nakhtmin) was an administrator during the reigns of the Pharaohs Hatshepsut and Thutmose III, who was eventually “promoted to one of the highest positions in the administration as the overseer of the double granary of Upper and Lower Egypt” (Díaz-Iglesias Llanos and Méndez-Rodríguez 2023). Minnakht was buried in Theban Tomb 87 (TT87), located in the “Tombs of the Nobles” necropolis at Sheikh Abd el-Qurna.

TT87 was discovered by archaeologist Robert Mond and published in 1905 (as reported in Díaz-Iglesias Llanos and Méndez-Rodríguez 2023, see Mond 1905). The tomb was excavated by Heike Guksch of the German Archaeological Institute from 1977 until 1988. The tomb contained numerous painted scenes displaying garden scenes and funerary rituals (e.g. see copies of some of the tomb paintings made in 1921 by Charles K. Wilkson, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544601).

In 1978 the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA) purchased nine stolen fragments of TT87’s paintings from an Amsterdam-based art dealer (Fatsis 1988), apparently without knowing that they came from TT87. The fragments were never displayed within the museum (Gold 1988). At some point after the purchase, a curator at the MFA raised concerns about the paintings and their origin (Washington Post 1988). Upon discovering that the paintings likely came from TT87, the MFA voluntarily offered to return them to Egypt (Gold 1988).

The MFA’s director at the time, Alan Shestack, told the press that “he was not surprised that it took 10 years for curators to raise questions” about the fragments (Gold 1988). He stated that museums were short staffed and that it could take them years to get around to investigating new acquisitions (Gold 1988). This is obviously not an ideal scenario if pre-purchase due diligence is considered important to preventing the traffic in looted cultural objects’.

In December 1988, the fragments were returned to Egypt (Washington Post 1988). Shestack stated that the dealer who sold them the fragments “signed an agreement guaranteeing that the art was not stolen” (Shestack quoted in Washington Post 1988). However, by the time of the return the dealer was reported to have passed away (Fatsis 1988) which meant that the MFA could not ask for their money back (Washington Post 1988). Shestack told the press at the time that the fragments were “not very expensive” (Shestack quoted in Gold 1988).

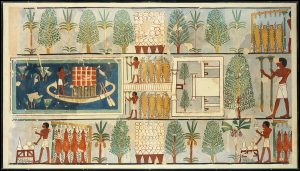

[Image (Public Domain): Facsimile of the tomb’s paintings made in 1921; they may not represent the pieces that were stolen and returned.]

Works Cited

Díaz-Iglesias Llanos, Lucía and Daniel M. Méndez-Rodríguez (2023) Epigraphical Study of the Burial Chamber Belonging to Nakhtmin (TT 87): Materiality and Scribal Hands. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 82(1).

Fatsis, Stefan (1988) Boston Museum to Return Purloined Tomb Artifacts. Associated Press. 30 December.

Gold, Allan R. (1988) Museum Returning Antiquities to Egypt. The New York Times, 30 December.

Mond, Robert (1905) # Report of Work in the Necropolis of Thebes During the Winter of 1903-1904. l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale. 5–76, fig. 11, pls. IV–IX.

Washington Post (1988) Boston Museum to Return Stolen Art. The Washington Post, 30 December. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1988/12/31/boston-museum-to-return-stolen-art/f381c52a-7344-4219-afc3-745564352e4e/. Accessed on 29 August 2023.