The antiquities trade: Four case studies

Brodie, N. (2014) ‘The antiquities trade: four case studies’, in Chappell, D. and Hufnagel, S. (eds.) Contemporary Perspectives on the Detection, Investigation and Prosecution of Art Crime. Oxford: Ashgate, pp. 15–36.

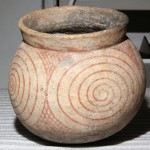

Antiquities are generally held to comprise individual objects or parts of larger objects or structures that were made in ancient times (antiquity). examples might include ceramic or metal vessels, statues or parts of statues, or broken off pieces of architecture. although the term ‘antiquities’ is in general usage, and seems to enjoy some consensus of understanding, there is no agreed date-threshold for separating antiquities from ‘non-antiquities’, and so it should be born in mind that the term is subject to a certain fluidity of meaning. Since at least the eighteenth century, antiquities have been taken from archaeological sites, monuments and museums and traded internationally. Over time, as the material damage caused by the looting of antiquities came to be recognized, proliferating national and international laws placed the antiquities trade under progressively stronger statutory regulation, so that increasingly it has been made illegal. Nevertheless, this regulation has not succeeded in controlling or reducing the trade, and since the 1950s the material volume and monetary value of the trade have risen at an alarming rate. and while traditionally, the antiquities trade has been in the hands of specialist dealers, the increasing availability of illicit antiquities on the open market has opened opportunities for more routine criminal involvement and profit.

This chapter examines by way of four case studies various harmful manifestations of the antiquities trade. First, it recounts the tale of the now famous Euphronios krater, bought by the Metropolitan Museum of art in 1972 for $1 million, and explains how the looting and trade of antiquities like the Euphronios krater can damage archaeological heritage, thereby weakening or compromising historical scholarship. Not all traded antiquities are as valuable as the Euphronios krater, nor are they important enough to be named individually, but the second case study, examining archaeological site looting in Jordan, shows how the trade of less valuable antiquities can still be profitable, and how their extraction can still cause enormous damage. The third case study moves away from questions of archaeological damage and historical scholarship, and considers how antiquities might be exploited by more commonplace episodes of financial crime, in this case the possible misuse of material donations to Californian museums for tax fraud. Finally, following and elaborating upon the problem of fraud, the fourth case study introduces the subject of fake antiquities by way of a description of the so-called Persian Mummy, discovered in Pakistan in 2000, and the further challenges to historical scholarship that they pose.