Río Azul Mask

Author: Donna Yates

Last Modified: 14 Jun 2015

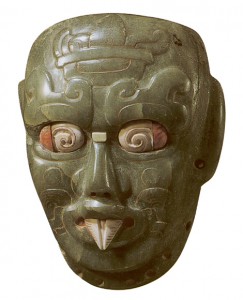

A Classic Maya funerary mask apparently looted from the Guatemalan site of Río Azul and illicitly trafficked into the United States and then Europe.

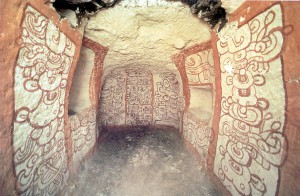

The most famous apparently-looted object from the site of Río Azul is a mask made of fuschite[1] depicting Kinich Ahaw, the sun god. The mask seems to have been the death mask of a lord, and text on the back of the object confirms that it belonged to a Río Azul ruler (Adams 1999: 216). Adams speculates that the mask may have come from Tomb 1, as inscriptions in that tomb claim the sun god as an ancestor. If this is true, inscriptions in the tomb would date the mask to the Early Classic Period (Adams 1999: 216). At least two other jade objects from Río Azul have appeared in a private collection in Brussels: matching earflares that bear the Río Azul emblem glyph (Adams 1999: 217). There is some speculation that these relate to the jade mask and may have come from the same body.

The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that the mask came into the possession of a businessman named Peter G. Wray from Scottsdale, Arizona (Salisbury, 1986). Wray offered the mask and other items in his collection for sale through Andre Emmerich’s New York Gallery in 1984. According to Adams (Mintz 1985), archaeologist Ian Graham saw the mask for sale in the gallery, noting the Río Azul emblem glyph on its back. The mask failed to sell for the asking price of $470,000 during an April 1984 exhibition, although a Río Azul tripod vase also from the Wray Collection was sold to the Detroit Institute of Art at that time (Detroit Institute of Art 2012). At some point later the mask was reportedly sold for $35,000, and was moved to an unknown location (Salisbury 1986). Around this time National Geographic Magazine and the Guatemalan Institute of Anthropology and History offered $10,000 ‘for a photograph that shows the object in the undisturbed location in which it was found’ (Salisbury 1986). While there was no proof that such a photograph existed, the call was meant to produce evidence that would conclusively prove that the mask came from Guatemala and thus was the property of that country. No photograph was forthcoming.

During the 1990s the mask was rumoured to be in a private collection in Germany, having passed through Switzerland (Adams 1999: 216). In late 1999 the piece surfaced in a temporary exhibition in the Barbier-Mueller Pre-Columbian Art Museum in Barcelona where it was seen by several Guatemalan government officials (Hernández Sánchez 2008: 4). In July 2001, the government of Guatemala issued a legal claim for the Río Azul mask as well as 11 other Guatemalan items in the Barbier-Mueller collection (Hernández Sánchez 2008: 60; Valdés 2006: 94). This process, documented extensively in Hernández Sánchez (2008), came to an end in 2002 when a Barcelona court denied Guatemala’s claim, stating that any alleged crime would have occurred outside of Spain’s jurisdiction (Hernández Sánchez 2008: 61). The mask is thought to still be in the Barbier-Mueller collection, having been moved back to Switzerland, but its exact whereabouts remain unknown (Hernández Sánchez 2008; Nessi 2008).

Was the mask looted? How can we know?

The mask from Río Azul is a good example of how we might apply the principle of Occam’s Razor to hypothetical provenance and provenience claims in illicit antiquities cases. In other words, the most plausible scenario is the one which demands the fewest assumptions based on the available evidence. One might naturally ask the question ‘do we know this mask was looted from the site of Río Azul in the late 1970s and illegally smuggled into the United States shortly after that time?’ The answer is that we do not know, but the available evidence strongly points towards this as the most likely explanation of the recent history of the mask. The argument for looting, based on the evidence, would proceed roughly as follows:

- The Maya were a literate culture; an inscription on the back of the mask bears the emblem glyph of Río Azul[2] and the name of a ruler sometimes rendered as Zak Balam or Sak Balam (White Jaguar), also called Ruler X or Governor X (Hernández Sánchez 2008: 85).

- Due to the complex nature of the language, a grammatically and contextually correct Maya inscription is nearly impossible to fake; the mask is not considered to be a forgery.

- Zak Balam’s name and image appear on Stela 1 at Río Azul, a monument that is still at the site, confirming he was a ruler of that polity. The date on that Stela is 26 March 393 AD.

- The looted Tomb 1 in structure C-1 at Río Azul was an elite tomb. The date 9 September 417 AD is painted on the wall of the tomb in a context that would closely align with the symbolic birth of the individual interred there into the next world, in other words his death (Acuña 2007: 12).

- Both the dates and matching water/swamp mythology iconography, would allow for the individual mentioned on the mask and Stela 1 to have been buried in Tomb 1.

- Maya masks are typically found in funerary contexts associated with the individual that they depict or name (the mask of Pakal of Palenque for example).

- Tomb 1 had not been looted in 1962 when the site was visited by Richard E.W. Adams (Adams 1999: 4).

- Tomb 1 had been looted in 1981 when Ian Graham visited the site (Adams 1999: 4).

- Guatemala claimed ownership of all archaeological remains, even undiscovered remains in 1947 via Article 1 of Decreto No 425.

- The mask was not seen on the art market or in a private or public collection until the early 1980s (Mintz 1985; Salisbury 1986).

On the basis of this progression of analysis, a reasonable person might conclude that the mask was looted from Tomb 1 at Río Azul sometime between 1962 and 1981 (probably in the late 1970s based on the date it ‘surfaced’, or became publicly known), was illegally smuggled out of Guatemala (as it was found after 1947) and trafficked into the United States.

In most jurisdictions where repatriation claims are litigated, a dispossessed country must prove that an artefact came from a specific archaeological site after a specific date (usually the date that the country in question claimed ownership over archaeological objects). This is, essentially, how the claimant state proves its ownership of the piece and thus that the piece had been stolen. If clear proof of these stipulations is not forthcoming, it is common for courts to rule in favour of the current possessor of the object (a good example of this is Peru v. Johnson). It is not unusual for current possessors of cultural objects to raise the possibility of hypothetical situations to explain how the object may have legitimately come to them, which test the bounds of plausibility to their limits. Some of the arguments in the case of the Weary Herakles fall into this category for some commentators.While the Río Azul may appear on the face of it to be a likely case of looting and illegal smuggling, the burden of proof in these disputes is high and on the claimant.

References

Acuña, Mary Jane (2007), Ancient Maya Cosmological Landscapes: Early Classic Mural Paintings at Río Azul, Peten, Guatemala (University of Texas: Masters Dissertation). <http://www.seiselt.com/gradstuds/maryjaneacuna/Pages/Acuna_MA%20Thesis%20UT_Rio%20Azul%20Tombs.pdf>, accessed 6 August 2012.

Adams, Richard E.W. (1999), Río Azul: An Ancient Maya City (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press).

Detroit Institute of Art (2012), ‘Tripod Vessel with Slab-legs’, Website of the Detroit Institute of Art <http://www.dia.org/object-info/9feb1644-2f68-46af-a76b-9fa53aef695d.aspx?position=1>, accessed 6 April.

Hernández Sánchez, Edgar Herlindo (2008), ‘La Máscara de Río Azul: Un Caso de Tráfico Ilícito del Patrimonio Cultural de Guatemala’, (Universidad de San Carlos De Guatemala: Licenciado Dissertation). < http://biblioteca.usac.edu.gt/tesis/14/14_0407.pdf>, accessed 6 August 2012.

Mintz, Bill (1985), ‘Art dealers in U.S. allegedly foster looting of Mayan city’, The Houston Chronicle, 24 March.

Nessi, Lorena (2008), ‘Herencia Maya en España’, BBC Mundo, 29 March, p. 2-3.

Salisbury, Stephan (1986), ‘The Struggle to Save a Past From Plunder’, The Philadelphia Inquirer, 11 May.

Valdés, Juan Antonio (2006), ‘Management and Conservation of Guatemala’s Cultural Heritage: A Challenge to Keep History Alive’, in Barbra T. Hoffman (ed.), Art and Cultural Heritage: Law, Policy and Practice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 94-99.

[1] A green stone; the mask is sometimes reported as being made from jade

[2] Chinchilla poetically renders this portion of the mask text as ‘Its image, its son, its god, of Río Azul’ (see Hernández Sánchez 2008).