Toi moko

Tattooed and preserved Māori heads, traded primarily in the mid-nineteenth century and the subject of a number of recent repatriation requests.

A seemingly pan-human fascination with death and a desire to possess the exotic has produced both a licit and an illicit market for ethnographic and archaeological human remains. The collecting of such remains peaked in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a by-product of European and American colonialism. However, these items are still bought and sold on the international art and antiquities market. Of particular interest, both during the age of empire and now, are remains that display pre- or post-mortem cranial modification or preservation: mummies, modified skulls, inlayed teeth, shrunken heads, etc. Stripped of their cultural contexts and moved into a foreign setting, these remains play to a Western love of the grotesque and/or reinforce a certain stereotype of so-called savagery. The Māori Toi moko were collected for this reason; Toi moko are preserved tattooed heads.

What is moko?

Businessman Shane Te Ruki says that his moko ‘reflects his passion for kaupapa maori’ from the Waikato Times 2009

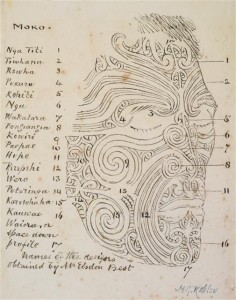

Māori carved facial tattooing (tā moko) was a highly-personal and sacred sign of rank in pre-European New Zealand (Palmer and Tano 2004). In Māori culture, the head is considered to be the most sacred body part and the act of tattooing the head further enhances this sacredness (Newell and King 2006). The intricate patterning of facial moko produced what can be likened to fingerprints: individuals were identifiable by their moko, even after death. Both men and women received facial moko, however male moko tended to cover much of the face while female moko was normally concentrated on the lips and chin (Palmer and Tano 2004). Moko began to decline among men in the 1860s[1], however women continued to receive moko into the 20th century (Palmer and Tano 2004). Tā moko has recently been revived as an outward symbol of modern Māori identity.

The heads of family members or conquered enemies with moko were often preserved, a process that involved smoking the head and drying it in the sun (Mulholland 2011). The resulting preserved, skin-covered skull would still display the tattooing that allowed identification of it as an individual and, thus, a revered deceased person could remain a member of his community (Newell and King 2006). Depending on the circumstance, these Toi moko as the heads are called, would be used in ceremonies (Mulholland 2011) or, in the case of trophies of war, be displayed on posts as a point of derision (Newell and King 2006).

Toi moko as ethnographic curios

The idea of Toi moko being ‘savage’ ethnographic curios and items of trade entered Western popular culture quite early on. For example, the character of Queequeg in Herman Melville’s 1851 novel Moby-Dick, himself a heavily-tattooed native of a fictional Pacific island, is introduced to the readers by a barman:

This here harpooneer I have been tellin’ you of has just arrived from the south seas, where he bought up a lot of ‘balmed New Zealand heads (great curios, you know), and he’s sold all on ’em but one, and that one he’s trying to sell to-night, cause to-morrow’s Sunday, and it would not do to be sellin’ human heads about the streets when folks is goin’ to churches (Melville 1851: 20).

The first sale of a Toi moko to a Westerner dates to the very first contact between Europeans and Māori. The English naturalist Joseph Banks purchased several of them on 20 January 1770 during Cook’s first voyage to New Zealand[2]. It is thought that these were enemy heads being traded as further insult (Cook 1770). In the mid 19th century, during New Zealand’s Musket Wars, the sale of Toi moko to westerners was one of the most effective ways that Maori groups could acquire the ammunition and arms that they needed for protection (Newell and King 2006; Palmer and Tano 2004). Reportedly, two heads bought one gun (Hubbard 2008). Even prominent period collectors acknowledged that the sale of Toi moko was done in an effort to avoid annihilation (Palmer and Tano 2004).

During the peak sale period for Toi moko (1820 to 1831) it is thought that hundreds of heads were purchased and exported. The European desire for Toi moko was such that there are reports of slaves being tattooed after their death to produce heads for commercial sale resulting in tattooed heads covered in iconographic errors (Palmer and Tano 2004). By April 1831, the problems surrounding the sale of Toi mokoi were such that the General Sir Ralph Darling, Governor of New South Wales, banned their further sale in Sydney, the main route through which Toi moko were trafficked to Europe (Newell and King 2006; Palmer and Tano 2004). The export of Toi moko is thought to have been slowed significantly by the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi.

The Robley collection of Toi moko

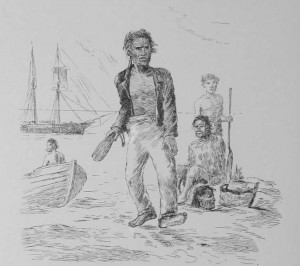

‘Bargaining for a head, on the shore, the chief running up the price’ a sketch Robley originally published in 1896

One of the most prominent collectors of Toi moko was Major-General Horatio Gordon Robley. He collected around 40 Toi moko, primarily from sales within the United Kingdom, despite his long tenure in New Zealand (Hubbard 2008). In 1908 Robley attempted to sell his collection to the New Zealand government for £1,000 before ultimately selling 39 heads to the American Museum of Natural History for £1,250.

An interesting scene of Toi moko sale can be seen in an 1896 sketch by Robley entitled ‘Maoris bargaining about mokomokai’. In it a Māori man carrying a mere (flat club) and wearing western trousers but no shirt approaches the artist and a Māori woman sits behind a decapitated Toi moko that is presumably for sale. Both Māori, themselves, have tattooed faces. A ship is seen in the background.

Modern auctions and outcry

On 16 June 1980, a Toi moko was offered at Sotheby’s London in a sale of so-called ‘Primitive Works of Art’ (Sotheby’s London, 16 June 1980: Lot 63). Valued at £5,000 to £7,000, the Toi moko is described as being the property of the Marquis of Tavistock. This head did not sell at Sotheby’s, however it was re-offered at Bonham’s, London, in May 1988. Largely due to the work of the late musician Dalvanius Prime, himself both Māori and a descendant of H.G. Robley, this head was removed from the sale and eventually returned to New Zealand for reburial. This is thought to be the last Toi moko offered at public auction (Newell and King 2006).

Repatriation

The return of Toi moko has been one of the primary concerns of New Zealand’s repatriation efforts, a process that many attribute to the work of Prime (Mulholland 2011). Te Herekiekie Herewini, head of the repatriation team at Te Papa (the national museum of New Zealand), has noted a change in attitude concerning the return of Toi moko. ‘If you asked them 20 years ago, most of them would probably have said a flat no, but if you asked them within the last three or four years, there’s been a change in the thinking of the museums themselves’ (Herewini quoted in Hubbard 2008). Because of the unique patterning of Toi moko, iwi and whānau (group and family) affiliations and even distinct individuals are sometimes identified among them. Thus, at times, it is possible to return a Toi moko to its direct descendant. However, the majority of repatriated Toi moko cannot be specifically identified and are kept in respectful storage at Te Papa and are not available for viewing (Hubbard 2008).

Resources

Cook, James (1770), ’20 January 1770′, The Endevour Journal.

Hubbard, Anthony (2008), ‘The trade in preserved Maori heads’, Sunday Star Times, 16 January.

Melville, Herman (1851), Moby-Dick; or, The Whale (New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers).

Mulholland, Malcom (2011), ‘Mokomokai are home where they belong’, The Timaru Herald, 19 May.

Newell, Jenny and King, Jonathan (2006), ‘Human Remains from New Zealand: Briefing note for Trustees’, (The British Museum).

Palmer, Christian and Tano, Mervyn L. (2004), ‘Mokomokai: Commercialization and Desacralization’, Prepared Report (Denver: International Institute for Indigenous Resouce Management).

[1] There is some evidence that suggest that the decline in popularity of male moko at that time was due to a general desire to not have one’s head become an item of commercial sale (Palmer and Tano 2004).

[2] ‘Some of the Natives brought a long side in one of their Canoes four of the heads of the men they had lately kill’d, both the Hairy-scalps and skin of the faces were on…’ (Cook 1770).