Jiri Frel

Jiri Frel was curator of antiquities at the J.Paul Getty Museum between 1973 and 1984, and was associated with several irregularities regarding museum acquisitions.

Frel arrived in the United States in 1969 from Czechoslovakia, where for the previous twenty years he had been professor of classics at Charles University in Prague. After brief stints at Princeton University’s Institute for Advanced Studies and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, he was appointed by the Getty Museum in 1973 as its first Curator of Antiquities (Hoving 1996: 282; Felch and Frammolino 2011: 26). His work in assembling a collection of antiquities for the Getty was associated with suspicions of malpractice, and in 1984 he was placed on paid leave (Felch and Frammolino 2011: 53). He subsequently resigned in 1986 (Felch and Frammolino 2011: 82).

Central to Frel’s strategy for building up the Getty’s collection was a scheme he devised that exploited US federal law on tax relief for charitable donations. He entered into an agreement with antiquities dealer Bruce McNall, who was partner with Robert Hecht at Summa Antiquities, whereby McNall would locate individuals willing to donate antiquities to the Getty in exchange for a tax deduction, and arranged through Summa to supply them with the necessary material. Frel would provide an appraised value for the donation that would be far in excess of the price paid to Summa (Felch and Frammolino 2011: 32). McNall received 10 percent commission on the price paid to Summa by the donor (Frammolino 2006). The scheme’s trial run was with movie producer and coin collector Sy Weintraub, who received a tax deduction of $1.65 million USD in the first year, and $1.2 million in the second year for a pair of fourth-century BC fresco fragments he had bought from Summa for $75,000 and donated to the Getty at an appraised value of $2.5 million (Felch and Frammolino 2011: 33). Word of these profits spread, and McNall was subsequently able to attract other Hollywood celebrities and tycoons to join the scheme (Felch and Frammolino 2011: 33). As time went on, McNall’s partner Hecht would ship material directly to the Getty, where it could remain on loan until such time as McNall could arrange a donor (Felch and Frammolino 2011: 35). Frel would also supply inflated appraisals for pieces bought at public auction—for example a Roman head bought for $900 was valued at $45,000, and two sarcophagus fragments bought together for $4,000 were valued at $40,000 (Hoving 1996: 287). Frel initially obtained appraisals from New York antiquities dealer Jerome Eisenberg (Glueck 1987), but after acquiring a stock of Eisenberg’s letter-headed notepaper, began to prepare them himself, instructing his secretary to forge Eisenberg’s signature (Felch and Frammolino 2011: 43). Between 1973 and 1985, Frel attracted 6,453 objects from dozens of donors, valued at just over $14 million (Hoving 1996: 286; Felch and Frammolino 2011: 36). By way of comparison, Thomas Hoving estimated that during his ten-year term (1967–1977) as director, the Metropolitan Museum’s twenty-two departments had between them received only $6 million worth of donated artefacts (Hoving 1996: 286).

Frel also used his donation scheme to fool the Getty’s trustees. He would gain their approval for a price to be paid for an acquisition in excess of what he had agreed with the vendor, and use the difference to buy more material from the dealer concerned. This material could also be fed into the museum through the donation scheme (Hoving 1996: 329; Felch and Frammolino 2011: 44).

It has been claimed that Frel’s schemes were intended to establish the Getty as a major scholarly museum, and thathis object in acquiring the donations was to establish a ‘research collection’ that would never have been approved by the trustees, who were interested only in high-priced display objects. Although he seems not to have benefited personally from the donations, he did receive payments from antiquities dealers as commission for helping to arrange sales to collectors or to the Getty (Hoving 1996: 288; Felch and Frammolino 2011: 329).

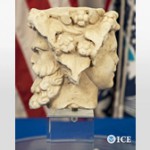

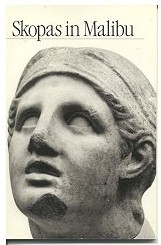

In 1983, several Getty donors were interviewed by the Internal Revenue Service, and the Getty launched an internal probe into Frel’s activities. He was placed on paid leave in 1984, whereupon he departed for Europe. He stayed in Paris for a few months, and then at the Castelvetrano home of Italian antiquities dealer Gianfranco Becchina, before settling in an apartment in Rome. He resigned from the Getty in 1986, and it was subsequently revealed that he had been responsible for the acquisition of several high-profile and expensive, possible fakes, including a fragment of a supposedly sixth-century BC marble funerary relief, a marble head said to be by the fourth-century BC Greek sculptor Scopas, and the Getty Kouros (Hoving 1996: 289; Felch and Frammolino 2011: 55). Frel died in 2006 (Frammolino 2006).

Thomas Hoving later discovered that not all of the ‘donors’ had been aware of their donations made in their names, and that, presumably in consequence, tax deductions had not been claimed on all donations. He surmised that the donation scheme might actually have been part of a larger plan concocted by Frel and Gianfranco Becchina to launder or render invisible to Swiss tax authorities the large profits Becchina had made selling the Getty what are now alleged to be fake artifacts (Hoving 2009

References

Felch, Jason and Frammolino, Ralph (2011), Chasing Aphrodite: The Hunt for Looted Antiquities at the World’s Richest Museum (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt).

Frammolino, Ralph (2006), ‘Jiri Frel, 82; Colorful curator who left Getty under a cloud’, Los Angeles Times, 13 May. http://articles.latimes.com/2006/may/13/local/me-frel13, accessed 17 July 2012.

Glueck, Grace (1987), ‘A curator upsets the Getty’, New York Times, 14 February. http://www.nytimes.com/1987/02/14/arts/a-curator-upsets-the-getty.html, accessed 17 July 2012.

Hoving, Thomas (1996), False Impressions: The Hunt for Big Time Art Fakes (London: Andre Deutsch).

Hoving, Thomas (2009), Artful Tom, A Memoir: 31. The Getty Wars [online text]. http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/features/hoving/artful-tom-chapter-thirty-one6-12-09.asp, accessed 25 May 2012.