Ocucaje Cemeteries

Nazca and Paracas cemeteries that were looted throughout the 20th century for sellable ancient textiles; aslo the site of a famous class of fake antiquity, the so-called Ica Stones.

The Ocucaje district, one of the 14 districts Peru’s the Ica Province, is a wine-producing area that sits on the edge of an arid region known as the Ocucaje desert. Its name is derived from the Hacienda Ocucaje, now located on the Panamerican Highway about 35 km south of Ica and 130 km northwest of Nazca. The Nazca and Paracas Cultures, among others, inhabited the Ocucaje region and the arid climate has led to the preservation of such rare cultural materials as textile, feather work, and wood implements. The sites in the region have been heavily looted. From the early 2oth century onwards, the owners of the Hacienda Ocucaje are known to have collected pre-Conquest cultural material and are thought to have participated in the looting of nearby sites (Proulx 2006: 21; Dawson 1979).

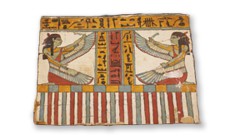

The majority of looted Ocucaje material comes from several known pre-Conquest cemeteries at sites such as Cerro Max Uhle and Cerro de la Cruz. Tombs at these sites are typically rectangular with adobe brick walls and form two superimposed chambers separated by logs or canes (Peters 2000). The tombs tend to be individual burials. These burials are primarily associated with Nazca and Paracas cultures.

In January and February of 1901, archaeologist Max Uhle excavated several cemeteries near the Hacienda Ocucaje. At the time, the hacienda was managed by a Dr. Ernesto Mazzei with whom Uhle was obliged to share the contents of some of the graves that he located (Proulx 2006: 21). Uhle also purchased Nazca cultural material from a local dealer which indicates that sites in the area were being looted at that time (Proulx 2006: 22).

The Soldi Collection

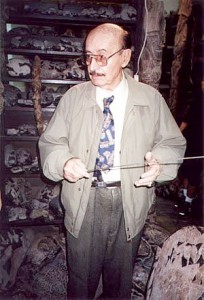

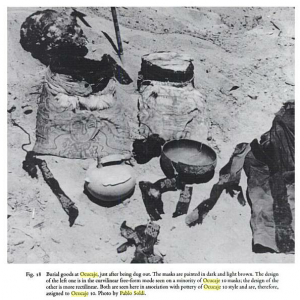

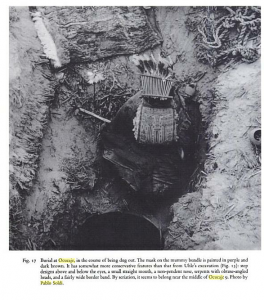

Looting Photo taken by Soldi and given to Dawson for The Junius B. Bird Pre-Columbian Textile Conference, May 19th and 20th, 1973

In 1941 an Ica-based dealer in antiquities named Pablo Soldi allegedly began a large-scale operation to commercially loot archaeological sites in the Ica Valley (Dawson 1979). This venture lasted approximately 18 years and during this time the Ocucaje cemetery sites identified by Uhle as well as others were hit. Soldi sold a number of mummy masks from Ocucaje to Paul Truel, then a co-owner of the Hacienda Ocucaje. Subsequent Ocucaje material passed through Soldi’s hands and ended up for sale on the United States art market (Dawson 1979). In 1960 archaeologist L.E. Dawson obtained two photographs from Soldi depicting burials unearthed by his team of diggers (Dawson 1979).

By 1965 a portion of Soldi’s collection had found its way to the National Textile Museum and another portion was sold to the American Museum of Natural History (Dawson 1979; King 1983). According to the records available on the American Museum of Natural History website, the museum purchased over 100 objects from Soldi in 1959, most of which are listed as having come from Ocucaje sites such as Cerro Max Uhle (American Museum of Natural History n.d.).

Ocucaje Material on the Market

Examples of Ocucaje textiles have appeared on the art market for the past few decades. For unknown reasons, they are some of the only South American objects that have site name provenience listed in high-end auction catalogues. For example, on 24 November 1986 (Sale N05579, Pre-Columbian Art, Sotheby’s New York), two textiles offered from the estate of actor Zero Mostel were listed as coming from Cerro Max Uhle (lots 11 and 12). Only one of the fifty nine other South American antiquities lots offered at that sale contained provenience data as specific as a site name, a gilt copper headband listed as being from the heavily looted site of Loma Negra. It is impossible to tell if Mostel’s textiles truly came from Cerro Max Uhle, but the inclusion of the site name suggests a certain degree of comfort with the looting incident that produced the pieces.

Recent reports indicate that looting continues at Ocucaje. The area is said to be poorly policed and signage instructing members of the public to stay off the site is barely visible (Noticias de Nasca 2010). Locals report that looting operations at Ocucaje sites start at around 11 pm (because by then dogs have stopped barking) and digging continues until around 3 am (Noticias de Nasca 2010).

Fakes and Dinosaurs: The Ica Stones

Ocucaje is also the place of origin for a massive amount of popular hoax artefacts known as the ‘Ica stones’. These engraved andesitic stones show images such as humans hunting dinosaurs and are said to date to the pre-Conquest. Javier Cabrera Darquea, a Peruvian physician who collected and popularized the Ica stones, purchased 341 of them from Pablo Soldi and his brother Carlos with the understanding that they came from their excavations of pre-Conquest graves (Coppins 2001). The Soldi brothers are said to have told Cabrera that they could not get archaeologists interested in the pieces. Cabrera abandoned his medical practice, converted the lower floor of his home into a museum, and devoted the rest of his life to these stones (Bruhns and Kelker 2010: 184). He reportedly collected around 11,000 of them and around 50,000 are thought to be circulating around the world (Bruhns and Kelker 2010: 185–186).

In 1975 two farmers, Basilio Uschuya and Irma Gutiérrez de Aparcana, informed noted pseudoscientist Erich von Daniken that they had forged the stones based off of images of dinosaurs from comic books. They later claimed they only said that the stones were forged to avoid being arrested for antiquities trafficking. In 1977 Uschuya crafted an Ica stone on film for a BBC documentary entitled ‘Pathways to the Gods’ (Coppins 2001). That same year Uschuya was arrested for selling archaeological material by Peruvian authorities. He signed a legal confession admitting that the Ica stones were a hoax and was released (Bruhns and Kelker 2010: 184).

Real Fossils at Ocucaje

Finally, the Ocucaje desert is host to a significant amount of illicit excavations for fossils (Romero 2010). Fossils, like antiquities, are classified as national patrimony under Peruvian law and, thus, are not exportable. However recent reports indicate that the region is not effectively policed and fossil digging goes largely unpunished (Romero 2010).

References

American Museum of Natural History (n.d.), ‘Anthropology Collections’, Website of the American Museum of Natural History <http://research.amnh.org/anthropology/>, accessed 29 June 2012.

Bruhns, Karen O., and Nancy L. Kelker (2010), Faking the Ancient Andes, (Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press).

Coppins, Filip (2001), ‘Jurassic library – The Ica Stones’, The Fortean Times, October. <http://www.forteantimes.com/features/articles/259/jurassic_library_the_ica_stones.html>, acessed 2 August 2012.

Dawson, Lawrence E. (1979), ‘Painted Cloth Mummy Masks of Ica, Peru’, in Anne P. Rowe, Elizabeth P. Benson, and Anne-Louise Schaffer (eds.), The Junius B. Bird Pre-Columbian Textile Conference, May 19th and 20th, 1973 (Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks), 83-104.

King, Mary Elizabeth (1983), ‘The Painted Mummy Bundles of Ocucaje (Peru)’, Indiana, 1(8), 243-266.

Noticias de Nasca (2010), ‘Huaqueros en Ocucaje’, Noticias de Nasca, 5 November.

Peters, Ann H. (2000), ‘Funerary Regalia and Institutions of Leadership in Paracas and Topara’, Chungara, 32(2), 245-252.

Proulx, Donald A. (2006), A Sourcebook of Nasca Ceramic Icongraphy: Reading a Culture Through Its Art (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press).

Romero, Simon (2010), ‘Buried in Peru’s Desert, Fossils Draw Smugglers’, The New York Times, 12 December.