Giacomo Medici

Giacomo Medici is an Italian antiquities dealer who was convicted in 2005 of receiving stolen goods, illegal export of goods, and conspiracy to traffic.

Note: Seized images of illicit antiquities which lead to the eventual conviction of Medici can be found in our Tracking Illicit Antiquities section.

Medici started dealing in antiquities in Rome during the 1960s (Silver 2009: 25). In July 1967, he was convicted in Italy of receiving looted artefacts, though in the same year he met and became an important supplier of antiquities to US dealer Robert Hecht (Silver 2009: 27-9). In 1968, Medici opened the gallery Antiquaria Romana in Rome and began to explore business opportunities in Switzerland (Silver 2009: 34). It is widely believed that in December 1971 he bought the illegally-excavated Euphronios (Sarpedon) krater from tombaroli before transporting it to Switzerland and selling it to Hecht (Silver 2009: 50).

In 1978, he closed his Rome gallery, and entered into partnership with Geneva resident Christian Boursaud, who started consigning material supplied by Medici for sale at Sotheby’s London (Silver 2009: 121-2, 139; Watson and Todeschini 2007: 27). Together, they opened Hydra Gallery in Geneva in 1983 (Silver 2009: 139). It has been estimated that throughout the 1980s Medici was the source of more consignments to Sotheby’s London than any other vendor (Watson and Todeschini 2007: 27). At any one time, Boursaud might consign anything up to seventy objects, worth together as much as £500,000 (Watson 1997: 112). Material would be delivered to Sotheby’s from Geneva by courier (Watson 1997: 112).

In October 1985, the Hydra Gallery sold fragments of the Onesimos kylix to the J. Paul Getty Museum for $100,000, providing a false provenance by way of the fictitious Zbinden collection, a provenance that was sometimes used for material offered at Sotheby’s (Silver 2009: 145; Watson and Todeschini 2007: 95). The Getty returned the kylix to Italy in 1999.

In 1986, bad publicity surrounding the sale of looted Apulian vases at Sotheby’s London caused Medici and Boursaud to part company, and Medici bought the Geneva-based Editions Services to continue consigning material to Sotheby’s (Silver 2009: 147; Watson and Todeschini 2007: 27; Watson 1997: 117, 183-6). From 1987 until 1994, he was also consigning material to Sotheby’s through other ‘front companies’, including Mat Securitas, Arts Franc and Tecafin Fiduciaire (Watson and Todeschini 2007: 73). He developed a triangulating system of consigning through one company and purchasing the same piece through another company. There were two potentially positive outcomes of this triangulation manoeuvre: first, it artificially created demand, suggesting to potential customers that the market was stronger than it actually was; and second, it was a way of providing illegally-excavated or -exported pieces with a ‘Sotheby’s’ provenance, and, in effect, laundering them (Watson and Todeschini 2007: 135-41).

By the late 1980s, Medici had developed commercial relations with other major antiquities dealers including Robin Symes, Frieda Tchacos, Nikolas Koutoulakis, Robert Hecht, and the brothers Ali and Hicham Aboutaam (Watson and Todeschini 2007: 73-4). He was the ultimate source of artefacts that would subsequently be sold through dealers or auction houses to private collectors, including Lawrence and Barbara Fleischman, Maurice Tempelsman, Shelby White and Leon Levy, the Hunt brothers, George Ortiz, and José Luis Várez Fisa (Watson and Todeschini 2007: 112-34; Isman 2010), and to museums including the J. Paul Getty, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

In 1995, a Sotheby’s London auction catalogue advertised for sale a sarcophagus recognized by the Carabinieri to have been stolen from the church of San Saba, in Rome. Sotheby’s informed the Carabinieri that it had been consigned by Editions Services (Watson and Todeschini 2007: 19). This was around the same time that the ‘organigram’ had been discovered, revealing Medici’s central position in the organisation of the antiquities trade out of Italy (Watson and Todeschini 2007: 19), and putting the evidence together, the Carabinieri decided to act. On 13 September 1995, in concert with Swiss police, they raided Medici’s storage space in the Geneva Freeport, which comprised five rooms with a combined area of about 200 sq metres (Silver 2009: 174; Watson and Todeschini 2007: 20). One room was equipped as a laboratory for cleaning and restoring artefacts, another was fitted out as a showroom, presumably for receiving potential customers (Silver 2009: 180-1). In January 1997, Medici was arrested in Rome (Silver 2009: 175-6), and in July 1997, his Geneva storerooms, which had remained sealed since 1995, were opened again for the process of examination and inventory.

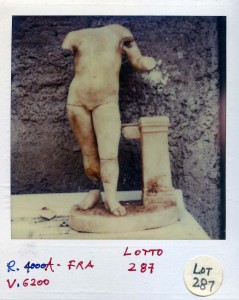

The official report of the contents of Medici’s storerooms was submitted in July 1999. The storerooms had been found to contain 3,800 whole or fragmentary objects, more than 4,000 photographs of artefacts, and 35,000 sheets of paper containing information relating to Medici’s business practices and connections. The artefacts were mainly from Italy, but there were also hundreds from Egypt, Syria, Greece and Asia. The Swiss authorities turned over Italian material to Italy, but returned the rest to Medici (Silver 2009: 192). The photographs were mainly Polaroids, showing what appeared to be illegally-excavated artefacts, sometimes with several views of the same one, in various stages of restoration. Some artefacts were shown still covered with dirt after their excavation, some fragmentary, and others cleaned and reassembled prior to sale (Watson and Todeschini 2007: 54-68). In 2002, Carabinieri raided Medici’s home in Santa Marinella (Watson and Todeschini 2007: 200).

Medici was charged with receiving stolen goods, illegal export of goods, and conspiracy to traffic, and his trial in Rome commenced on 4 December 2003. On 12 May 2005, he was found guilty of all charges. The judge declared that Medici had trafficked thousands of artefacts, including the sarcophagus fragment that had started the investigation, and the Euphronios (Sarpedon) krater (Silver 2009: 212). He was sentenced to ten years in prison and received a €10 million fine, with the money going to the Italian state in compensation for damage caused to cultural heritage (Silver 2009: 214). In July 2009, an appeals court in Rome dismissed the trafficking conviction against him because of the expired limitation period, but reaffirmed the convictions for receiving and conspiracy. His jail sentence was reduced to eight years, but the €10 million fine remained in place (Scherer 2009). In December 2011, a further appeal failed (Felch 2012).

The evidence recovered during the investigation into Medici’s business was instrumental in forcing several museums and private collectors to return artefacts to Italy, and triggered further investigations and ultimately the prosecutions of Marion True and Robert Hecht.

References

Felch, Jason (2012), ‘Quick takes’, Los Angeles Times, 20 January. http://articles.latimes.com/2012/jan/20/entertainment/la-et-quick-20120120, accessed 18 July 2012.

Isman, Fabio (2010), ‘Looted from Italy and now in a major Spanish museum?’, Art Newspaper, 13 July. http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/Looted%20from%20Italy%20and%20now%20in%20a%20major%20Spanish%20museum?/21261, accessed 17 July 2012.

Scherer, Steve (2009), ‘Rome court upholds conviction of antiquities dealer’, Bloomberg.com, 15 July. http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=asneBHwVx9wU, accessed 17 July 2012.

Silver, Vernon (2009), The Lost Chalice (New York: HarperCollins).

Watson, Peter (1997), Sotheby’s: Inside Story (London: Bloomsbury).

Watson, Peter and Cecilia Todeschini (2007), The Medici Conspiracy (New York: Public Affairs).